August 17, 2021

Translation and interpretation are not the same thing as language justice. This is an important lesson learned from Cambridge’s citywide language justice initiative.

As Executive Director of Cambridge’s Family Policy Council, I strive to be a catalyst—coordinating the resources of multiple city departments to deliver a more powerful impact for children, youth and families than any of these departments could deliver on their own. The Council is chaired by the Mayor and includes family and youth representatives who contribute alongside elected officials and top decision-makers including our Assistant City Manager for Human Services and Finance, Chief Public Health Officer, Police Commissioner, Director of the Public Library, Superintendent of Schools, and representatives from business, philanthropy, university, and state agencies.

This powerful collaboration produces policy and program recommendations with built-in support from those who will be charged with implementing them.

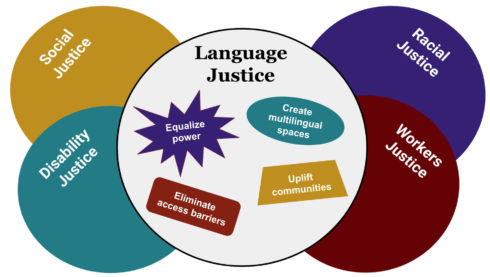

Our current focus is language justice—the right to communicate, to understand and to be understood in the language(s) in which a person feels most comfortable. This includes the communication rights of individuals with preferred languages other than English as well as persons with communication-related disabilities.

By focusing on language justice as a City, we believe we will see an increase in the number and ways in which people in Cambridge interact with and are connected to their local government, schools, health systems, nonprofits and other essential services.

We are midway through a process of self-study and policy development, and many concrete and technical solutions have been identified. Through our partnership with Cortico, a deeper and more compelling story has emerged as those farthest from Language Justice have had space to share their experience and envision solutions.

Last fall, a newly-formed Language Justice Working Group began a discovery process aimed at identifying key questions, methods, and venues for gathering information from families and providers/agencies. We took an inventory of existing efforts and researched what other communities were doing. We also reviewed existing data and surveyed providers to pinpoint challenges and quantify the level of interest and willingness to improve practices.

Our research revealed that about 8% of the Cambridge population does not speak English very well – and that linguistically isolated individuals are more likely to be technologically isolated – with at least 15% lacking any access to the internet or computers at home. We also discovered that only half of city, school and community providers know what language-access resources are available to respond to these families.

Among organizations responding to our survey, many of those who offer translation and interpretation rely on staff members who receive no additional training or pay to perform this needed service. And, at least 50% do not proactively offer language access supports, relying on individuals to know they can ask for this type of assistance.

In other words, we already know what the problem is – and most organizations would like to work toward a solution. To understand why this problem is so persistent, and to look more deeply for solutions, we needed to turn to those most affected. Through a series of conversations that use Cortico technology and process, we have been turning to communities most directly affected by language barriers – including individuals with preferred language other than English, people with disabilities, and the translators, outreach workers and family liaisons who work most closely with them.

Whereas a focus group is designed to elicit specific information, Cortico’s conversation model is designed to get people to tell their stories, which gets us closer to the heart of the matter. From our conversations with Spanish-speakers and with bilingual English speakers, we learned that one of the most painful aspects of a language barrier is the frustration and impatience manifested by English-speakers.

Asked to share barriers to communication, Samsun used the word “suffering” in describing the impact of the impatient and rapid pace that is prevalent among Cambridge and Boston English Speakers.

Also counseling patience, Virginia recommends smiling and being as patient as possible when communicating with someone who speaks another language.

Playing these voices in a Family Policy Council meeting brought a more human dimension into our conversations about language justice. As we develop policy and best practices , we now better appreciate that we will need to build in conversation and support around creating environments and interactions that set people at ease. We need community members to realize that even if it takes longer for us to understand their viewpoints and needs, this information is important to us and well worth waiting for.

More than 70 languages are spoken among the families of students attending the Cambridge Public Schools, and there will always be languages not accounted for as we build towards greater inclusion of all cultures and families. Our goal should therefore not only be technical compliance with a set of translation procedures, but a goal of achieving understanding.

Our conversations with bilingual and Spanish-speaking community members surfaced some easy-to-implement tips about making website translation easier to find and providing visual cues and icons on printed communications that sometimes overflow children’s backpacks when they come home from school each day. Experienced family liaisons like Greta also shared that they strive to communicate as clearly and plainly as possible in English.

In conversations, many providers reflected aloud about their own practices. Deirdre described feeling impressed, inspired, and committed to implementing cultural proficiency training that includes aspects of language justice and customer service even in more operational departments like the Department of Public Works , Traffic department, or Community Development Department (CDD).

Even those organizations who have implemented clear technical solutions for providing translation, interpretation and disability accommodation sometimes struggle to achieve language justice. Maria, who speaks Portuguese, explains that obstacles can arise if the translator and person seeking information are from different countries or speak different dialects.

Translators and interpreters also need to be trained and supported to understand where people are coming from. Carole, who has worked for years with our city’s Community Engagement Team, advocates for comprehensive training to support empathy and awareness in addition to language and translation skills.

The above highlight from Carole also points to a related need…

City policies in Cambridge prioritize availability of low-income housing, and as a result we are a very economically diverse city. We are also a city with abundant resources,yet still struggle to achieve language justice. What’s missing, our conversations are telling us, is a shared understanding and commitment to rising to the challenge of full equity and inclusion.

Denise, another family liaison working with diverse communities, calls for greater leadership and coordination on this issue:

Language Justice cannot be an afterthought – it must be a primary thought, she says.

So far, I have focused on the challenges and opportunities related to building a culture that supports communication and values understanding – and have de-emphasized the technical challenges of communicating across language barriers. However, the technical challenges of achieving language justice really should not be understated.

Even working with Cortico – an amazing resource that added to the efficiency and effectiveness of our engagement with community members – had limitations that are entirely technical in nature. Cortico’s technology is so far designed for English and Spanish only, and for verbal communication that can be facilitated by a sign language interpreter speaking the words of a deaf person – creating distance between speaker and spoken word. Other languages could be recorded, translated, and then uploaded into the system – but the most useful features of Coritco’s Local Voices Network platform would be lost in this process.

As a partner, Cortico is actively working on the very same issues that Cambridge is facing – so we know we’re not alone as we move towards solutions. This work is challenging, but it is very much worth it.

By addressing the needs of persons with hearing and vision disabilities and all individuals with a preferred language other than English, ALL community members will be better understood, valued, and have equitable access to all available services and resources in Cambridge. In addition, if the City of Cambridge designs and implements a thoughtful, strong language access plan, then all community members will be understood, valued, and have equitable access to all available services and resources. Cambridge will be a stronger, more welcoming, and more just city.

Nancy Tauber is Executive Director of the City of Cambridge’s Family Policy Council, where she has spearheaded efforts to improve policies and resources available to families. Past successes have included implementing a citywide Family Engagement statement, building collaboration to promote math literacy through the Math Matters for Equity Project, and launching a Cambridge-specific and family-focused website, FindItCambridge. Prior to this role, Nancy served two terms on the Cambridge School Committee (School Board), where she was instrumental in reforming the city’s struggling and inequitable offerings for middle school education. She also spent 12 years as a middle school Social Studies teacher in the City of Newton, MA.